In the spring of 1952, R.M. Schindler received a letter from Arthur Drexler, director of the Department of Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art. MoMA, which had scarcely acknowledged Schindler, was planning to produce an update of Built in USA, the 1944 survey organized by Elizabeth Bauer Mock, and would like to consider his work for the upcoming exhibition. Schindler’s response was prompt and concise, neatly typed, and nearly plaintive in its forthrightness:

“In 1921, with the impact of California fresh on my mind, I built my own house, trying to meet the character of the locale,” he stated, laying out his early concepts while leading up to more recent developments.

About that time several attempts were made to develop an architectural expression for California. Frank Lloyd Wright tried by introducing modernized versions of Aztec details. This was a superficial attempt, completely false historically, climatically and functionally, and died at birth. Later (1928) Richard Neutra imported the international style, which he himself admits, belatedly, violates the local character.

In my own house (1921) I introduced features which seemed to be necessary for life in California: an open plan, flat on the ground; living patios; glass walls; translucent walls; wide sliding doors; clerestory windows; shed roofs with wide shading overhangs. These features have now been accepted generally and form the basis of the contemporary California house.1

Despite this cogent statement, accompanied by a strong record of significant work, Schindler was not selected by Drexler and his co-curator, architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock, for Built in USA: Post War Architecture (1953).

For more than 20 years, Schindler had intermittently launched a series of spirited, cantankerous exchanges with the museum. In 1932, when his work was omitted by curators Hitchcock and Philip Johnson from The International Style: Architecture Since 1922, he challenged the museum’s Eurocentric bias, big name hunting, and disdain for the West Coast. As architectural historian Kathryn Smith has so wryly and rightly pointed out, not only did Schindler’s first independent building embody the exact criteria designated by the curators—“volume rather than mass, regularity over symmetry, and the avoidance of applied ornament”2—the daring and original Schindler House had been completed in 1922, the proclaimed debut year for International Style.

“IS THE EXHIBITION ANOTHER ‘INTERNATIONAL STYLE’ BALLYHOO?” demanded Schindler in a 1935 letter to MoMA curator Ernestine Fantl. “I AM DEFINITELY TRYING TO ESTABLISH AN AMERICAN TRADITION OF MODERN WORK AND DO NOT WANT TO JOIN A GROUP, WHICH MERELY COPIES EUROPEAN FUNCTIONALISM.” Schindler’s single-spaced correspondence, banged out on a portable typewriter locked into upper case, appears to shout from the page, resolute and almost comically bombastic, delivering a blast of rigorous ideas spiked with zesty contemporary slang. “Not a ballyhoo,” demurred Fantl in her reply. “Plan to show west coast architecture in the East.” Contemporary Architecture in California, a small circulating exhibition on display in New York for three weeks in October 1935, featured models and documentation of Hollywood movie sets, commercial buildings, private homes, and public schools; photographs of and plans for three Schindler-designed residences and his interiors for Sardi’s restaurant were included, but there was no mention of his own house and studio.3

In February 1932, just as MoMA’s International Style exhibition opened and the ballyhoo was kicking into high gear, the Philadelphia-based T Square journal (founded by Paul Cret and George Howe as a forum for architectural “discussions and recriminations”) quietly published A Cooperative Dwelling, a short presentation, composed by Schindler, outlining his radical program for the Kings Road House—four individual studios designed for two couples, a communal kitchen, and outdoor living spaces.4 That same year, Pauline Gibling Schindler, the architect’s estranged wife and indefatigable champion, writing about modern California architects for Creative Art Magazine (New York), declared: “The work of Schindler results from a life picture which is revolutionary, and which differs strongly from the current mechanistic view of life which functionalism, perhaps abjectly, serves.”5

R.M. Schindler (born 1887, Austria) received a progressive architectural education in Vienna—studying with Otto Wagner at the Academy of Fine Arts, heeding thought-provoking lectures given by Adolf Loos, and poring over the 1910 Wasmuth Portfolio, a particularly splendid introduction to Frank Lloyd Wright’s recent Prairie Houses. In 1914, months before the outbreak of the Great War in Europe, he signed on for a job with a Chicago architectural firm, sailed to the United States, and began to study Wright’s buildings firsthand. “His art is spatial art in the true sense of the word,” he reported back enthusiastically to his friend Richard Neutra. “The room is not a box—the walls have disappeared and free nature flows through his houses as in a forest.”6 Although Schindler wanted to return to Vienna, his plans were dissuaded by the war and then diverted by a job offer from Wright. Hired in 1918, he entered Wright’s office in the midst of two major commissions: the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo and Olive Hill. The latter, Wright’s first Los Angeles project, was an ambitious proposal developed by left-wing oil heiress Aline Barnsdall for a theater community on a 36-acre site in Hollywood.

While employed by Wright in Chicago, Schindler met Sophie Pauline Gibling; a Smith College graduate known as Pauline, she was a political activist and radical aesthete who taught music at Jane Addam’s Hull-House, the first social settlement created for immigrant families. As writer Esther McCoy—Pauline’s colleague and Schindler’s longtime chronicler—pointed out, he preferred, like T.S. Eliot and H.L. Mencken, to be known by his initials. He disliked the name Rudolph, was called Michael by friends, and used “R.M.S.” as his signature. The couple married in August 1919. The following year, Wright sent Schindler to Los Angeles to superintend construction on Olive Hill, and the newlywed couple found their lives unexpectedly and irrevocably transplanted.7 They toured the Southwest, settled into Los Angeles, and in 1921, after a revelatory camping trip in Yosemite National Park, decided to build their own studio residence. In a memorable 1916 letter home, Pauline had announced: “One of my dreams, Mother, is to have, someday, a little joy of a bungalow, on the edge of the woods and mountains near a crowded city, which shall be open just as some people’s hearts are open, to friends of all classes and types.”8 In Los Angeles, Schindler envisioned that desire as “a real California scheme,” articulating the essential requirements of a camper’s shelter—“earth at the back, light at the front”—and incorporating a social agenda intended for hosting events and temporary residents.

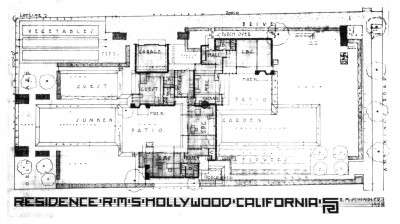

During the last two months of 1921, Schindler designed his “Cooperative Dwelling for Two Young Couples.” The layout was a low-slung pinwheel scheme comprised of three L shapes pivoting around a double fireplace, encompassing three private patios and four individual studios—one each for the Schindlers and the other two for their friends—Pauline Schindler’s college classmate Marian Da Camara Chace and her husband Clyde Burgess Chace, a trained engineer employed as a contractor/builder. Together, they purchased a 100 by 200 foot parcel from businessman Walter L. Dodge; the sale price of $2750 was divided between the Schindlers, who invested $2350 (with financial support from the Giblings) and the Chaces ($400). The parcel was part of a real estate tract dubbed Hollywood Acres and billed as the “newest of the high-class foothill subdivisions” being developed by Dodge and Judge A.M. Stephens.9 Dodge’s nearby residence (950 Kings Road, Irving Gill, 1916) was considered one of the first truly modernist houses in the West. The neighboring neo-colonial (850 Kings Road, Frank T. Kegley, 1914) of Attorney Raymond Stephens, son of the judge, was sited on two acres with a tennis court and orchard. For an architect about to set up his own practice, the professional advantages of living and working in an accessible, “middle class section” of a city were apparent to Schindler. The area, originally settled in the late nineteenth century, was a booming garden spot well served by the interurban railway system, electric utilities, and the West Los Angeles Water Company; eight miles northwest of downtown, the unincorporated town was called Sherman prior to being re-christened West Hollywood in 1925.

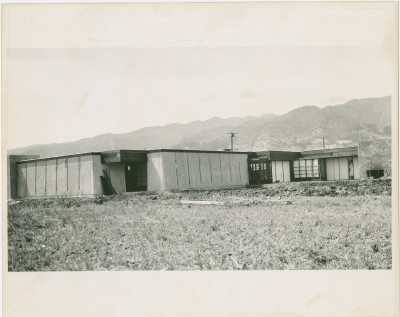

The nearly flat half-acre lot on Kings Road was also well suited to constructing a house utilizing Schindler’s version of Slab-Tilt construction, a quick and economic method used to build barracks during the Spanish-American War. Tapered concrete wall panels were cast on site and lifted into place using a block and tackle. Chace, who had worked on several of Gill’s concrete buildings, recalled that the concrete for the Kings Road House was poured into frames lined with paper, creating a pattern of creases and rivulets for the interior surfaces, which were later buffed with a wax finish. Writing to Neutra in Europe, Schindler apprised him of the project and its progress: “My house is an interesting experiment and a success. The concrete walls were poured in sections on the concrete floor and then lifted… It eliminates all the cost of form work. I put glass between the panels with the result that the 3-inch slots repeat decoratively.” The vertical slivers of glass created ribbons of light, and clerestory windows hung horizontally beneath the redwood ceiling. His plan, explained Schindler, was “a simple weave of few structural materials which retain their natural color and texture throughout”: concrete, glass, raw canvas, copper, and redwood treated with a wire brush to accentuate the grain. The concrete floors and walls would provide “an everlasting backbone.” Non-bearing walls and room partitions were Japanese-style sliding redwood-framed screens fitted with glass or Insulite, a water-proofed fiberboard (patented 1915) produced from paper mill waste and advertised as a low-cost lumber substitute and “a sound deadener.” Schindler’s design for Kings Road, noted Esther McCoy, “combined the two darlings of the modern movement: the Japanese and concrete. A contradiction of terms, he deliberately contradicted the light with the solid.”10

Unlike Gill’s mastery of a minimalist aesthetic based on closed forms and framed views, Schindler’s planar geometry was abstract and airborne, utilizing spatial voids as building material and dissolving thresholds and the separation between indoors and out. When McCoy first visited the house in 1941, she remarked, “In that Puritan period of modern design, this house was mysterious and disturbing. With the floor on the same plane as the hearth, and the hearth on the same plane as the patio, fire joined earth.” Each studio—identified in the floor plan by the initials of the four original occupants—was deemed a “universal space” and such conventional notions as parlor and master bedroom were eliminated. Two “sleeping baskets,” trellised open-air porches, were added to the north and south sides of the roof. Near the end of his life, in an undated handwritten postscript, Schindler confided: “My house was built outside L.A. and never needed a permit. Hope nobody catches on.”11

Before construction on the Kings Road House was completed, both Pauline Schindler (indicated as “S.P.G.” on the floor plan, which stands for her maiden name) and Marian Chace (M.D.C.) became pregnant, their babies due to arrive into a rather non-traditional, un-family home. Schindler, who often designed with the improvisational flair of a jazz player, carved out a little corner of the M.D.C. studio and named it the nursery. By the summer of 1922, the two young families had moved in and cooperative dwelling was put to the test. Although strained by financial struggles and medical concerns, the welcoming open setting and the city’s early avant-garde community proved invigorating.

As architect Harwell Hamilton Harris later remarked, “If any building can fire one with the passion for simple living and high thinking, this is it.”12 The studios and outdoor rooms came alive as active social spaces for dinners, performances of music and dance, political meetings, and readings that ranged from romantic poetry to fierce polemics. By design, the household population was constantly shifting. (A guest studio was part of the original plan.) In 1924, the Chaces had a second child and moved to Florida in order to join the Da Camara family business. Arriving from Europe in 1925, the Neutras—Richard, Dione, and their baby Frank—stayed in the small guest studio before taking over the Chace apartment. The Neutras spent four years at Kings Road, and it was a period marked by enormous personal tensions and remarkable professional accomplishments. There were outspoken disagreements about child-rearing (young Frank suffered from undiagnosed brain damage), feminism, and privacy; Dione Neutra gave birth to a second son, Dion; after suffering a breakdown, Pauline Schindler’s treatment with leading psychiatrist Dr. Ross Moore ended “in vain”; Neutra designed the Lovell Health House (1928–29) and published two influential books, Wie Baut Amerika? and Amerika; Schindler designed the Lovell Beach House (1925–26); and together, the two architects collaborated on a competition entry for the League of Nations Building (1926).

In August 1927, Pauline Schindler left her husband and Kings Road, taking their five-year-old son Mark with her. The Neutras moved out in 1930, and Richard embarked on a year-long trip to China, Japan, and Europe. When Neutra received sole credit for their League of Nations proposal, an irreparable rift in the friendship between the two architects occurred. The Neutras moved on and the Chace apartment was soon rented to John Bovingdon, a Harvard-educated economist and naturist interpretive dancer.

Schindler never went back to Europe, he lived and worked in the house on Kings Road until his death in 1953. Historian Robert Sweeney, president of the Friends of the Schindler House, has observed that, although Pauline Schindler led a fairly nomadic existence following the breakup of her marriage, she always returned to Kings Road. During the 1930s, she and Mark lived temporarily in the Chace apartment. By 1949, the house was divided by an interior wall: S.P.G. took up permanent residence on the north side and commandeered the kitchen while R.M.S. remained on the south. “It was as if the house stood up by the pressure of opposing wills,” said McCoy, who worked as a draftsperson in Schindler’s studio from 1944 to 1947.

For more than 50 years, the Kings Road House served as a vibrant salon, a creative milieu, a constant way station primed to shelter audacious ideas and intriguing personalities. Residents—including underemployed actors, fledgling architects, and progressive attorneys—stayed for weeks or years. Screenwriter Dudley Nichols and photographer Esta Varez (a former concert singer, born in England as Esta Julia Gooch-Collings) rented the Chace apartment for the year in 1932. Nichols later served as president of the Screen Writers Guild and became the first person to refuse an Oscar; in 1936, while the Guild was on strike, he turned down the Best Screenplay award for his work on John Ford’s classic Irish Republican Army drama The Informer (1935). Composer John Cage and Don Sample, an artist with an instinct about modern architecture, spent nine days at Kings Road in 1934. In the spring of 1935, Cage and fellow composer Henry Cowell organized a concert of gagaku, ancient Japanese court music. (The event was reported to have earned $13.)13 Galka Scheyer, art impresaria and promoter of the Blue Four, stayed in the guest studio in 1927 and reappeared in 1931. Samson DeBrier, an outre Hollywood salonist and self-described “celebrity warlock,” inhabited the guest studio during World War II. Journalist Anna Louise Strong, an ardent supporter of the early Soviet Union, stayed for three months while under contract as a screenwriter at MGM. The long and fascinating list goes on, a revolutionary twentieth-century guest book.

After Schindler’s death, Pauline continued to live in the house, staving off real estate developers, withstanding the grim consequences of the area’s re-zoning and the despoliation of Kings Road, and astutely hosting a new generation. When Kathryn Smith interviewed Pauline Schindler in 1975, she was offered the rental of an enclosed sleeping basket; she accepted. Architect Bernard Judge, ceramist Dora de Larios, and their daughter Sabrina lived in the Chace apartment from 1964 until 1971. In response to a 1980 survey about the property, Judge replied, “Although the house is too hot, too cold, and too wet, it is FANTASTIC. As an experience, poetic.” In 1970, following the ruthless demolition of Irving Gill’s Dodge House, plans were set into motion to recognize Schindler’s inestimable masterpiece and secure its future.

The Kings Road House remains the inspired prototype for West Coast modern design, a lyrical manifesto about the essence of shelter, architecture’s companionship with the environment, and the dynamics of constructed space. Schindler’s floor plan—the four studios for four working artists—was the realization of a social experiment, a lofty vision and earthbound presence that prized the solitude required for artistic production and encouraged the flow of ideas and open space.

In 1939, the spring/summer issue of Twice a Year—a New York-based journal of “literature, the arts, and civil liberties,” edited by Dorothy Norman—produced a special section on architecture. Among the contributors were William Lescaze, Walter Gropius, and Lewis Mumford.14 (Norman had asked Frank Lloyd Wright to contribute but he refused, complaining that the issue included too many representatives of the “foreign” International School of which he disapproved.15) The issue also featured a fold-out map, a guide to Outstanding Modern Buildings in America. Of the 136 homes considered noteworthy, 30 were located in Southern California, and 12 of those were designed by R.M. Schindler, including his own house at 835 North Kings Road.

1 Unless otherwise noted, all R.M. Schindler correspondence, R.M. Schindler Papers; Architecture & Design Collection; Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara.

2 Henry-Russell Hitchcock Jr. and Philip Johnson, with a preface by Alfred H. Barr Jr., The International Style: Architecture since 1922 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1932), 13; reprinted in Kathryn Smith, Schindler House (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001), 16.

3 Contemporary Architecture in California, MoMA Exhibition #42c (September 30–October 24, 1935), Exhibition History List, Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York, New York.

4 R.M. Schindler, “A Cooperative Dwelling,” T-Square 2 (February 1932), 20–21. Founded as T-Square Club Journal, issue 2 was titled simply T-Square. When Maxwell Levinson and R. Buckminster Fuller took over the publication in 1932, the magazine was renamed Shelter.

5 Pauline Gibling, “Modern California Architects,” Creative Art: A Magazine of Fine and Applied Art 2 (February 1932), 111–15.

6 Undated letter from R.M. Schindler to Richard J. Neutra, written between December 1920 and January 1921; reprinted in Esther McCoy, Vienna to Los Angeles: Two Journeys (Santa Monica, CA: Arts + Architecture Press, 1979), 130.

7 Kathryn Smith, 16.

8 Sophie Pauline Gibling to Sophie S. Gibling, n.d. (May 9, 1916), Pauline Schindler Papers; Architecture & Design Collection; Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara; reprinted in Robert Sweeney, “Life at Kings Road: As It Was, 1920–1940,” in R.M. Schindler, Elizabeth A. T. Smith, and Michael Darling, The Architecture of R.M. Schindler (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, in association with Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, 2001), 87.

9 Unsigned, “Country Place at City’s Edge: Sightly New Foothill Home of Local Attorney Set in Large Grounds,” Los Angeles Times, May 23, 1915, VI4.

10 Unless otherwise noted, all Esther McCoy quotations, Esther McCoy Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

11 R.M. Schindler, undated letter to Esther McCoy, circa 1952. R.M. Schindler Papers.

12 Harwell Hamilton Harris, quoted in Esther McCoy, The Second Generation (Salt Lake City: Gibbs M. Smith, Inc., 1984), 41; see also Harwell Hamilton Harris correspondence, Esther McCoy Papers.

13 Alan Rich, So I’ve Heard: Notes from a Migratory Music Critic (Milwaukee: Amadeus Press, 2006), 329.

14 Twice a Year 2, Spring–Summer 1939, New York, 106.

15 Dorothy Norman, Encounters: A Memoir (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1987).