The Architectural design concerns itself with “Space” as its raw material.

—R. M. Schindler1

This proposal describes an experiment where qualities and characteristics of the Rudolph M. Schindler’s Kings Road House are translated through the modality of sound using methods of sampling and transformation. Introducing ideas and concepts found within the context of the Schindler House, this proposal examines a few methods used to relate space and sound. It outlines a method for the multi-modal integration between architecture and sound using techniques of sampling and transformation and asks the questions: Can sound help us analyze and understand architectural structures differently? How can we translate between these two modalities and generate new spatial forms? Can these explorations provide the ability to re-imagine new ways for sound and architecture to relate throughout the unique context of the Schindler House? In addition to the described project is an accompanying proposal for an immersive installation within the spaces of the Schindler House. The goal of this proposal is to allow the experiences discovered through this experimental integration to become realized in real-time by those visiting this subtle and beautiful place.

Introduction

The Schindler House is a piece of architecture of delicate and deliberate finesse. Inspired by Yosemite National Park, methods of scale and material respond with poetics, perfect and true to a natural dialogue between space and the outside environment. Held inside its walls, one is never far from the presence of nature, its balance and beauty always peering inside and framing the space both inside and out. Composed through a grid, section, surface, and perspective, the Schindler House focuses on the presence of space and the surrounding landscape, the one enveloping the other.

Having been a key player in the modern living movement, the Schindler House once had a lively salon scene, serving as a meeting place to share food, wine and progressive thought amongst artists, architects, and political figures. The house also served as studios and intimate thinking spaces for the Schindler and Chace families, having a particular quiet and calmness to its atmosphere. While wandering through the interior spaces or meandering through the gardens outside, the delicate character of the subtle experience is unmistakable. Allowing the shining character of the Schindler House to lay undisturbed, this study brings a new attention to the sonic aspect of the house, to encourage a different beauty to radiate and bring pleasure to our minds and our ears.

Sonic Spaces

The intersecting space of nature, architecture, and sound is the canvas to re-imagine the Schindler House. Sound and silence, texture and color, frequency and amplitude are the materials to experience this new space. Between the grass and gardens lay the open textured surfaces of concrete, wood, and glass. These surfaces serve as mediators, letting the inside out and the outside in. Balance between the exterior and interior is key for one inspires and intersects the other. This in-between space is where the perceivable becomes presented, the “raw material” of sonic space.

This project amplifies a voice and color inherent to the Schindler House by embracing Schindler’s “Space as raw material” as the “medium of his art”, creating a transformative and evolving “architecture for the senses”.2 These sensual spaces are designed to be heard as well as seen and offer an environmental experience that is ubiquitous and liquid.3 There exists methodologies and contributions to this way of thinking about space and sound and one such method is known as Aural Architecture.

Aural architecture is a term used by Barry Blesser, a former MIT professor who published a book with Linda-Ruth Salter entitled Spaces Speak, Are You Listening? (MIT Press, 2006). This book explores spatial awareness from the auditory perspective and ideas of designing aural spaces that are socially and ecologically responsible. Blesser and Salter describe aural architecture as “the aspect of real and virtual spaces that produces an emotional, behavioral and visceral response in inhabitants”.4 Bissera Pentcheva, Associate Professor at CCRMA (Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics at Stanford) also uses the term in her research on the intersection of religious/sacred spaces, architectural psychoacoustics and multi-sensory aesthetics.5 These two examples along with other researchers from the disciplines of architecture, music, acoustics, and related fields are coming to discover the transvergence of sound and architecture in new ways.

Another methodology used to deal with intersection of sound and space is known as Soundscapes. A soundscape is an acoustic ecology arising from an immersive context that can include both natural and manmade environments. This term was coined by R. Murray Schafer and is discussed at length in his book The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World (Destiny, 1994). Soundscapes can be found in any existing environment. One can imagine what the landscape of a mountain meadow on a summer’s eve, or a boulevard in an urban center around rush hour might sound like; if that sonic composition was to be re-generated in a place other than where it was recorded, one can imagine they were back in that context. Soundscapes can also be generated to project a certain quality to a space such as Muzak (elevator music) or mediation and sleeping devices. Concepts behind soundscapes can also be overlaid to give sonic resolution to a current situation, offer cues to the visually impaired or others with healthcare related needs, or provide a backdrop for more conventionally heard music. It is important to note that Schafer’s book is focused on the fact that we need to be mindful of the sonic environment and that audible noise is polluting the natural world in the same way as light population and material waste.

Many significant artists have experimented with soundscapes and aural architectures either directly or indirectly as artistic, musical, or compositional endeavors including John Cage, R. Murray Schafer, Max Neuhouse and Luc Ferrari. Another important concept is the technique of Musique Concrete pioneered in the 1940s by Pierre Schaeffer. Musique concrete is a technique that uses and manipulates sound recordings in the generation of a new musical composition. This process of recording sounds and manipulating them for use in a new composition would come to be known as sampling and is an import concept in the generation of soundscapes, aural architectures and other multi-modal integrations. The early electronic composers of the twentieth-century including Schaeffer and Karlheinz Stockhausen greatly contributed to the knowledge and techniques of sampling and the advent of the computer in the latter half of the twentieth-century evolved these processes into the digital domain.

Sonic and Spatial Sampling

Sampling is an important technique used in this project, and the manipulation of the sampled characteristics give us the material to compose new forms and open the possibility of listening to space in new ways. In this project sampling is explored in two different capacities. The first is sonic sampling and uses particular microphones to listen and collect sounds from space. The second is spatial sampling and uses a 3D scanner to collect spatial data from the structure and volume of the space.

Sonic sampling is produced by recording the spaces of the Schindler House and adjacent gardens using microphones. Using contact microphones that sense the vibrations of the material to which they are attached, or condenser microphones, which have a very sensitive frequency and transient response. The sounds are recorded and catalogued for analysis and composition. These cataloged sounds are sampled from the natural surrounding environment such as grass, trees, bamboo, and the ambient outside atmosphere. Also used are the sounds found throughout the materiality of the Schindler House such as wood, glass, concrete, copper and the ambient inside atmosphere. The recorded sounds are analyzed using DSP (digital signal processing) techniques noting the sonic characteristics and unique sonic signature.

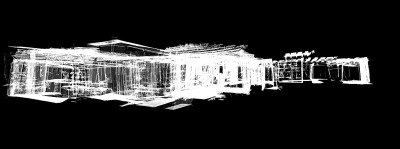

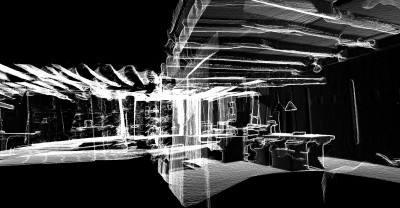

The second sampling method is spatial sampling and uses a 3D scanner to sample the spatial dimensions and colors of the Schindler House. Architects are accustomed to measuring an existing space (creating as-builts) and building a digital model from the collected measurements. 3D scanning offers an interesting step forward within this process and is being utilized in this process. First utilized for the purpose of meteorology and geography, these high-resolution scans generate a point cloud by taking millions of point measurements within a given range. This point cloud can then be used as a background to imagine new structures within the existing space and can offer a high degree of physical accuracy for making important design decisions. Bob Sheil at the Bartlett School of Architecture and Matthew Shaw and William Trossell’s ScanLAB have been experimenting with this technology providing interesting studies dealing with animation and zero tolerance production.6

Scanning the Schindler House provides us with a very accurate digital model that we can use to understand the existing structure and proportions not as it was drawn to be, but how it actually exists today. A high resolution 3D scan can capture the wear marks within the material, the slight differences between one element and another, and the physical artifacts that come with construction by hand. These processes and artifacts are described in more depth in the related project SoundScan.7 This Schindler Lab project explores using both sonic and spatial sampling together by applying the spatial scan to sound process, a modality that also has a high rate of fidelity. By using these two techniques and integrating the collected data, translational and transformational processes are then composed and compiled to generate new forms.

Translation, Transformation and New Forms

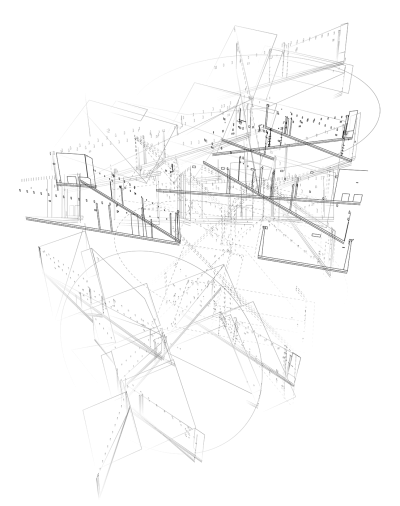

New material can be generated through translational and transformational processes to influence the design of new forms and sonic identities, as both architectural structures and compositional soundscapes. Since the sampled material is not a geometric primitive, but a complex assemblage with spatial characteristics and a unique temporal signature, the design process is open to new opportunities represented by the newly generated model.

The production of a representative model in this manner has been described by Julio Bermudez in the paper Data Representation Architecture: Visualization Design Methods, Theory and Technology Applied to Anesthesiology (Bermudez et al. 2000). Adrián J. Levy also uses the term Data Representation Architecture in his paper Real and Virtual Spaces Generated by Music (2003) and defines the term used by Bermudez as “the choice of any element from the everyday world, and the creation, by means of a digital process, of either a real or a virtual space”.8 This process of using a representative model encourages unique intersections between the modalities of sound and space. Each modality exists individually, but by collecting specific information from each modality, a new complexity is made possible within the design process that builds an intensity and intricacy not easily developed otherwise. By visualizing what is heard and hearing what is seen new possibilities can be explored.

The sonic information acquired from the microphones and the spatial and color information acquired from the 3D scan are translated and transformed using DSP techniques, allowing the sonic to transform the spatial and the spatial to transform the sonic. Once the transformations are established new sonic and geometric forms can be generated by converting the representative data into physical models. These synergetic forms offer new opportunities to explore meaning and significance by celebrating overlaps in the visual/spatial and sonic/temporal domains of architecture and sound.

A number of physical artifacts have been generated as part of this project. The first is a set of drawings generated from the translational and transformational information. These drawings illustrate spatial moments of the Schindler House processed through the modality of sound and time by transforming architectural plans, sections, and elevations into architectural scores from the sampled information. A soundscape is also composed from these transformations sampled from both material and nature, letting one hear the inhabited spaces. Lastly a video is composed using footage from the Schindler House to give a visual component to the soundscape. This video is meant to loosely simulate the experience one may have while being immersed in the installation component described throughout the proposal in the section below.

Soundscape of the Schindler House.

Composition and Interaction

The goal of this proposal is to realize in real-time the above mentioned work for those visiting the Schindler House.

The nature of music is a dynamic modality embedded within the temporal domain. To experience such a project it is necessary to allow the project to be experienced first in person and in real-time and not only by representative means. This is accomplished by expanding the mentioned sampling methods into an interactive component. A microphone matrix throughout the inside and outside of the house working with the 4 by 4 grid established by Schindler will be built to sample selected materials and spaces. An interactive program will collect these sounds in real-time and combine and process them with the 3D scan that was previously discussed. A soundscape is then composed and distributed through twelve speakers arranged throughout the Schindler House, eight inside (two within each studio space) and four outside (two in the front and two in the back gardens). Parameters based on the 4 by 4 grid, plan, material elements, sampled color, spatial rhythms and proportions would modulate the collected sounds and synthesize new ones.

Each room will hold a unique and dynamic spatial composition allowing visitors to experience an evolving immersive Soundscape. Layered with the sounds of knocking bamboo and the gentle vibrations of leaves, birds, voices, wind, and footsteps resonating through the material and recorded spatial proportions. The Schindler House will be turned into a musical composition, to be spatially explored and experienced, reflecting an aural architecture existing both inside and outside of the Schindler House.

Another component of this project could expand the sonic focus of this proposal into the domain of light and color. Experimenting with different visual experiences that would harmonize with the sonic composition and offer a narrated experience of the house through color and composition, affecting the reading of both inside and outside. Throughout the day, the spaces of the Schindler House will be filled with pattern and hue, sound and rhythm, layering colored shadows and sonic reflections across the concrete, wood and glass. While during the evenings the Schindler House will project and resonate the sonic character and spatialized harmonies into the surrounding natural environment creating an aural architectural performance.

Conclusion

This project and accompanying proposal experiment with the multi-modal integration of sound and architecture by translating and transforming sampled sonic and spatial information in the interest of reimagining the Schindler House. The Schindler House has been approached as a place positioned delicately within nature and the balance between the composed materials and natural environment provide the source of transformative material needed to explore this trans-disciplinary concept.

The methods of aural architectures and soundscapes have been introduced as related concepts for the application of sounds and sonic experience in the spatial realm. Musique concrete and its role in sampling along with transformative DSP processes have been described as techniques for the integration between the modalities of architecture and sound, generating new spatial forms throughout the unique context of the Schindler House. Questions of how sound can help us analyze and understand architectural forms related to Rudolph M. Schindler’s Kings Road House has been explored and possible directions have been outlined with the intention to continue additional in depth investigations into different processes and techniques.

Sound and the Schindler House, a spatial poem generated from a unique dialogue of proportional volumes, material fluctuations and natural contexts is scanned into patterns, sounds and rhythms, amplifying a voice inherent to this subtle and beautiful place. Schindler’s “raw material of space” is transformed here into an “evolving architecture for the senses”.9

1 R.M. Schindler, Manifesto. (Vienna: 1912)

2 Ibid.

3 Novak, M., Liquid Architecture in Cyberspace, in Benedikt, M. (ed.), Cyberspace: First Steps. (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1991)

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Sheil, Bob (ed.), High Definition: Negotiating Zero Tolerance. (London: Wiley, 2014)

7 Sciotto, F.M., Soundscan: Sound and Spatial Sampling (A Study of the Schindler House), ACADIA 14: Design Agency [Projects of the 34th Annual Conference of the Association for Computer Aided Design in Architecture. (Los Angeles: 2014)

8 Ibid.

9 R.M. Schindler, Manifesto. (Vienna: 1912)